Anne-Marie Duff: ‘We’re a country in trauma – the last 10 years have been a s*** show’

I can never see myself as being one of those people who goes on Question Time,” Anne-Marie Duff says, thoughtfully. “I wouldn’t feel that’s where I can articulate myself. But I guess I feel like a political person. I’ve never defined myself that way, but everything is a political issue. And I’m a mum, so everything cracks you open and forces you to think about your village, your global village. And you give a damn.”

She smiles and sits back in her chair. We’re talking in the bar of the Almeida, deserted except for the occasional delivery man. Politics is on the agenda because she is starring in Beth Steel’s epic new play The House of Shades, a saga of working-class life that tracks the fortunes of a family from the relatively hopeful mid-1960s, when a belief in progress for the poor seemed to be engrained in society, to the disillusion and frustration of 2019, when jobs and prospects have vanished.

Duff was attracted to the role of the damaged and damaging matriarch Constance at least partly because it focuses attention on a stratum of society rarely depicted on stage – and because it seeks to explain how we got to where we are today.

“It’s just a brilliant play about trauma. How everything is born of trauma. And how everything political is personal. The two are knotted very neatly together. You could say that right now because it feels like we are a country in trauma, doesn’t it? The last 10 years really have been a s***show. It’s like watching a freight train go through the station, and you think how many more bloody carriages? Just when you feel there is a sun peeping up over the horizon, then Putin goes f***ing mad. It’s been incredibly testing for all of us, hasn’t it?”

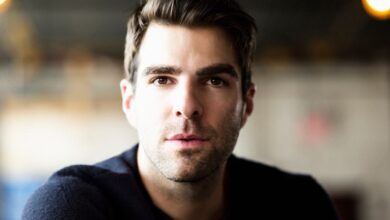

This is what it is like talking to Duff, who has been such a familiar figure ever since her breakthrough in Paul Abbott’s Shameless nearly 20 years ago. She is a collusive conversationalist, pulling you with her questions and phrases of agreement. It’s part of the everywoman quality that has made her not only one of our best actresses, but also one most able to evoke empathy and emotion, whether she’s playing kindly Ma Costa in His Dark Materials, or a drug-addicted mother in Sex Education.

It helps that she looks like a normal person rather than a screen star. “I’m not Botoxed up to the nines,” she says, when we start talking about what it feels like to be 51. “I made that decision, and some people think it’s bonkers, but it’s not stopped me getting work and it means that women on the street stop me and say ‘thank you very much’. It’s such an emotive thing, you know?”

But the sense that she understands ordinary people reaches to the heart of her talent. She seems to have an almost uncanny ability to let her face communicate thought and feeling. Simply to be the person she is playing, allowing all of their light and darkness to pour out of her. For all her success in film (The Magdalene Sisters, Suffragette) and on television (she is about to make her mark in a new Channel 4 series Suspect), it’s on stage that this skill is crystalised.

She has made a habit of choosing epic and often political plays, from George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan to Terence Rattigan’s Cause Célèbre about a woman wrongly convicted of murder to DC Moore’s Common (essentially about who owns England) and Ella Hickson’s Oil which spanned centuries in its explanation of our relationship with ‘black gold”.

The stage is where her political commitment finds focus. “It’s where I have any sense of purpose. Because story is important in changing things. It always has been. Look at Ken Loach’s Cathy Come Home which made people think about homelessness.”

The current slide of so many households into poverty is both part of the landscape of The House of Shades – and much on her mind. “I grew up in a household where we did have the gas cut off, where we did have to go without a lot. It’s always been my life. I’ve never not had to think about it.

“This is what people forget. It’s not just food banks, but how are you going to cook the food? How are you going to wash your kids? It’s just scary, isn’t it? The relentlessness of it. It makes you feel there is nothing you can do. But of course, people are innately good. We saw that during the pandemic. You’d be in a queue with 100 people in Sainsbury’s and only one would be being a pain in the arse. That’s what we have to hang on to.”

I wonder whether theatre is really the right forum for social issues. The audiences that habitually come are maybe not those who need their minds changing or their stories of hardship representing. Even here, her essential optimism shines through. “It is expensive, even subsidised theatre,” she says. “But that said, this could be a really good time for subsidised theatres, which often present more challenging work. People won’t be able to afford to pay £100 a ticket for theatre in the West End.

“When I was growing up, we didn’t go to the theatre. When you’re on the breadline, it can’t be a priority. That’s why we need theatre in schools and things like National Theatre Live and cheap ticket schemes to make things incredibly accessible to people.”

Her own upbringing in an Irish family in west London was impoverished in some ways, but rich in others. Duff remembers her father, a painter and decorator, sitting the family down to watch Franco Zeffirelli’s film Romeo and Juliet when it was on television; he encouraged her to read widely. “I was a bit weird. I read about people like [the 19th-century Italian actress] Eleanora Duse and Ellen Terry. It wasn’t like I was watching Lethal Weapon and thinking I want to be a star,” she says, with a laugh.

She began to act in youth theatre, and it was only later that she saw her first play thanks to a school trip to see Hamlet at the National Theatre, starring Daniel Day-Lewis. She was also influenced by British new wave films such as A Taste of Honey and Saturday Night and Sunday Morning. She’d like to do more cinema, “but film’s in a curious spot in the minute because there is a lot of safety round the superhero and the Marvel, DC Universe, and horror. I thought this year’s awards season was fascinating because it was a real sort of identity crisis.”

Anne-Marie Duff and Carey Mulligan in ‘Suffragette’

Television, on the other hand, is the thing these days. “And what is great about storytelling on screen is that there are a good deal more fantastic roles for women.” She points to Mare of Easttown as a TV show that people perhaps wouldn’t have made a decade ago, and we talk enthusiastically about the ground-breaking qualities of Sex Education, which she joined in series two as the irresponsible mother of the heroine Maeve. “I don’t think I’ve been stopped on the street more about anything since Shameless. People are just so fond of that show. Because it’s full of love. It isn’t cynically constructed.”

She is excited at the casting of one of Sex Education’s young stars Ncuti Gatwa as the new Doctor Who. “I grinned when I saw the news,” says Duff. “He’s so charismatic and brilliant. All those kids are brilliant – the nicest, most dedicated and most grateful in a really lovely way.”

Her own son, Brendan, from her 10-year marriage to the actor James McAvoy, is now 12. She and McAvoy met on the set of Shameless but divorced in 2016. Brendan lives with Duff but the actors bring him up together. “I love being a mum,” she says, with a grin. “I always knew I wanted to be one. But,” she adds quickly, “I’m also really interested in supporting women who don’t want to do that. I hate the area of nonsense and shame that’s around that.”

For Duff, though, motherhood “fits me well. The great thing about being a working mum is that you’ll never waste people’s time. You will be prepared. You know how each thing is precious. Every minute counts.”

Duff in ‘The House of Shades’ at the Almeida Theatre

Duff in the forthcoming Channel 4 drama ‘Suspect’