How scientists are taking ‘snapshots’ of prehistoric Britain

Scientists have been using sophisticated forensic techniques to create snapshots of life in prehistoric Britain.

By discovering, recording and analysing ancient footprints, they have been able to reconstruct in considerable detail specific moments in the lives of Britons who lived up to 8,500 years ago.

The research has been carried out on a beach near Formby, 12 miles north of Liverpool.

Hidden several metres below the surface of the region’s intertidal zones are tens of thousands of human and animal footprints left on long-buried mudflat surfaces. So rich was the ecosystem revealed that scientists believe that the area was “like a prehistoric British Serengeti”.

Thousands of years ago, the sun ‘baked’ those footprints and hoofprints hard in the hours after they were made, preserving their shapes before they were rapidly covered by a thin layer of sand by the next incoming tide.

Now a reverse process has been occurring – with storms and some tides uncovering, eroding and then re-burying the prints. It’s estimated that over the past two and a half decades, around 5,000 such prints have been briefly exposed before being broken up by wave action or reburied under sand.

But during the time that the prints have been exposed in a fully intact and visible state, scientists from the University of Manchester have been busy recording them.

Their ongoing research is revealing previously unknown data about the lives and times of the people who inhabited Britain’s coastal regions before, during and after the introduction of agriculture.

The oldest series of footprints, from 8,500 years ago, are those of a lone adult man who may have been stalking a large water bird, a crane – some of whose footprints are immediately adjacent to the human ones.

As part of his possible stalking operation, the footprint evidence shows that he walked very slowly and paused for a moment, perhaps in order not to alarm the bird. Cranes would have been a good source of meat and their spectacular feathers may also have been highly prized. Certainly, in many ancient cultures, crane feathers were used in ritual head-dresses.

Another moment in time, recorded by other footprints at the site, show two toddlers – each around two years of age – and five older children – aged seven to nine – almost certainly accompanied by an adult woman, probably their mother.

One day, likely a morning, in early summer around 8,100 years ago, they were walking as the tide was going out across a section of the mudflats which seems to have been crowded with herds of red and roe deer and giant wild cattle.

Interestingly, the cattle – dozens of whose hoof prints have survived – seem to have been particularly attracted to the wettest and muddiest parts of the mudflats. This is possibly because it offered them an opportunity to wallow in the mud, a specific known behaviour used by some types of cattle to rid themselves of ticks and tick larvae.

The footprint record also shows that there were other humans walking across the mud flats on the same morning as the mother and her seven youngsters were there. Those other individuals included a very tall lone adult male and four unaccompanied older children, aged between 10 and 14.

But prowling around on the mud flats that same morning was a lone wolf, who was no doubt looking for an animal or young human victim to kill and devour.

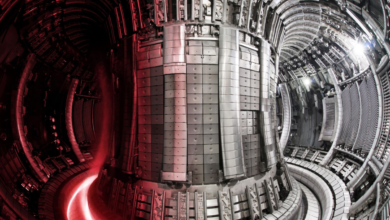

A footprint bed from the Mesolithic about 8500 years ago covered in red deer hoofprints

The presence of older children on the mud flats is particularly interesting. Usually children are virtually invisible archaeologically, but the new footprint evidence reveals that dozens of such unaccompanied Mesolithic children were operating both economically and socially on the mud flats. Their roles seem to have been to take care of younger children and almost certainly to gather shellfish or attend to fish traps.

On another early summer day around 5,300 years ago, the footprint record froze another random moment in time. It reveals a very brief meeting between an adult Neolithic female, her two children and another adult female. The footprint record shows that the first woman and her four and 10-year-old children paused briefly to greet the second woman, who passed them at right angles.

One of the most remarkable new pieces of information to emerge from the footprints research is the apparent height of some of the individuals. Forensic analysis of footprint data allows scientists to calculate how tall each person was.

Up until now, archaeologists had generally assumed that Mesolithic Britons were relatively short, but the footprint research suggests that at least some of these coastal people were actually very tall.

Red deer hoofprint in the ancient mud on Formby beach radiocarbon dated to about 8,500 years ago