‘The feminist in me is, like, hell yeah!’: Will men take the male contraceptive pill?

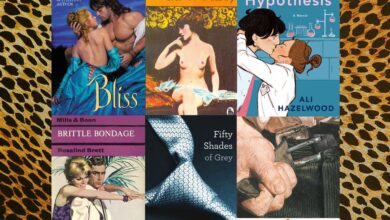

What is the greatest invention in history? Some might say the wheel, others sliced bread. But there is a strong argument that no single item has revolutionised society more than the contraceptive pill. Developed in the United States in the 1950s, the pill became a symbol of sexual freedom, integral to the women’s liberation movements of the Sixties and Seventies. Over 60 years after it was first introduced on the NHS, the pill is the main form of contraception for nearly a third of women of reproductive age in the UK, and more than 150 million women use it worldwide. Yet, while both the combined pill and “mini pill” are often held up as emblems of modernity – and as feminist milestones – the advent of oral contraceptives also put the burden for avoiding pregnancy on women. On one hand, the pill granted sexual freedom. On the other, the perception of sexual responsibility. And so, for many years, one question has dogged the medical establishment: what about the boys?

The idea of a male pill has been a dream for many years, but it’s also at times felt like wishful thinking – mainly from women who find the pill gives them spots, or blood clots, or depression. Successive trials of male contraceptives have stalled, despite results showing they would be effective in preventing pregnancy. This is due to the drugs being judged to have too many “unacceptable” side effects – an undeniable kick in the teeth for everyone forced into accepting the physical and emotional toll of many current contraceptive methods. Yet this could all be about to change.

Less than a fortnight ago, scientists revealed they’ve made a breakthrough in the creation of a male pill. So far, tests have only been carried out on mice, but they’ve been encouraging enough to suggest that an effective, reversible oral contraceptive for men might be on the market in the next few years. Unlike the female contraceptive pill, this new drug does not involve hormones, meaning it will not affect testosterone or have any hormonal-related side effects. Instead, the pill targets the “sperm-swim” switch, immobilising sperm for a couple of hours. The study, which was published on 14 February, found the medication is 100 per cent effective for up to an hour after being taken. After three hours the pill’s effectiveness dips to 91 per cent, and by 24 hours it appeared to have worn off fully. So, is a new sexual revolution around the corner? Will men be popping pills before sex? And how do they actually feel about it?

Dr Gareth Nye is a senior lecturer at Chester Medical School, specialising in maternal and fetal health and endocrinology. “The idea of a male contraceptive pill should be a fantastic thing,” he says. “For too long the burden of contraception has fallen to women and this may be in part due to the rather limited options for men – condoms or a vasectomy.” He says this status quo is mostly a product of physiology: “Men are constantly producing sperm, compared with women who are releasing one egg in a normally regular pattern.” So far, he says, “there have been difficulties in stopping the sperm production and retaining fertility, which is why progress has been slow.” He thinks the new male pill seems promising, but adds that it’s still a way off before humans can use it.

Aside from physiological issues though, Dr Nye believes widespread take-up will boil down to a question of risk versus reward. “I can imagine many men will weigh up the possible side effects of the drug against the benefits,” he says. “For women, the risks of unprotected sex are high and that just isn’t the same in men. So we see much more reluctance to engage with newer forms of contraception, which even has a risk of lowering libido, for example.” The most important question, then, is how much risk are men willing to take, to make their sexual partners’ lives easier.

“The feminist in me is, like, ‘hell yeah!’,” says Tim*, who’s in his mid-twenties. But he also notes that because he doesn’t currently take any medications, it would be a change in lifestyle. “I probably would have to get over thinking it would make me infertile.”

Harry*, who’s a similar age, shares similar concerns. “I’d love it if it was safe and effective,” he says, but also suggests “any new medicine will have problems gaining trust – obviously this pill has the potential to be massively profitable, which makes me think some companies may not fully investigate potential side effects.” Harry also raises an important issue about sexual safety. “I think there’s a danger that men would see it as a replacement for condoms,” he says, “which doesn’t do anything about STIs.”

James* is 42, and believes “any ability to take personal ownership would be a good thing and it seems equitable not to leave the imbalance with a female partner”. Initially, he seems fairly relaxed about the idea of potential side effects, claiming he would assess them “in the same way I would any other medical treatment”. He also admits, though, that there’s a limit to what he would put up with. “I’ve had partners for which the pill has played absolute havoc with their bodies, so I’ve absolutely supported them not using it at all and relying on other contraceptives. If that same havoc is in store for me, I’d definitely be cautious and see things like condoms as remaining a better option for us both.” While he thinks a male pill might helpfully change the conversation around responsibility for sexual health and safety, James also seems to partly confirm Harry’s concern that the male pill might be used as a replacement for condoms. “There is so much Andrew Tate-flavoured discourse around how much better [sex] feels without a condom,” he says. “Well, OK lads. There’s a pill for that now.”

It’s interesting to note that while all the men I spoke to were personally positive about the idea of taking a male pill – at least in theory – most also suggested that other men might be more reluctant. James, for example, predicted “a huge push back”, partly due to what he described as “ignorance as to what women have gone through”, and a general feeling of “this isn’t my problem”. Harry adds: “You’ll get men saying ‘it’s chill, I’m on the pill’, and they’re not.”

For some men, the decision to take the pill would depend on their relationship status. “If I was single I would not want to take the male contraceptive pill,” Greg* tells me. “But in a relationship, and certainly in my current one, where my partner is running out of contraceptives available to her, I would happily take the male pill – assuming it’s at the same risk level as the female one.” Again, though, Greg predicts he might be the exception rather than the rule. “My peers wouldn’t want to take the male pill because there’s already a female one,” he says. “We can acknowledge that’s a terrible argument, [but] it’s sadly the reality. However, I do think that opinion stems from a lack of understanding around the female contraceptive pill, as few men understand the true impact it can have on female lives.”

Greg’s girlfriend Phoebe, meanwhile, is all for it. “I think that the male contraceptive is the only way we can make meaningful progress in the way society views who bears the responsibility in sex over pregnancy, STIs, and female sexuality,” she tells me. For her, the choice is stark. “If a male pill isn’t available after I’ve had kids, I would be keen to have my tubes tied. The side effects of female contraceptives are so severe I can’t keep on them until menopause.”

Most research over the last five years shows that men would use the male pill in large numbers. A poll done by YouGov in 2018 showed that 30 percent of British men would be willing to take it – almost exactly the same percentage as the number of women using contraceptive pills in the UK today. Among 25 to 49-year-old men, this figure actually rises to 40 percent. More than anything, maybe what this shows is a growing understanding that the current state of affairs isn’t good enough.

Alice Pelton is the founder of The Lowdown, the UK’s leading reproductive and sexual health platform, and believes “the whole contraceptive space desperately needs innovation and investment”. She lays the blame at the feet of the pharmaceutical industry. “There are thousands of new and innovative ways to prevent pregnancy, but the industry doesn’t want to invest more time and money into developing new ways to stop people from getting pregnant, or investing in male contraceptive methods.” She says the reasons for this are manifold, from the fact contraceptives are expensive and difficult to develop, to pharmaceutical companies fearing that any new male methods will erode the established female contraceptive market. Aside from these practicalities though, Pelton believes the prospect of a male pill raises “fascinating questions” about sexual responsibility and agency. “Will we require men to carry around ‘contraceptive passports’ to prove their contraceptive status, like a vaccine? How would a woman feel taking a male partner home for casual sex if they say they’re on the pill?”

Contraception choices might be imagined as intensely personal, but they are also clearly connected to much broader questions about ethics, society, and bodily autonomy. Dr Elizabeth Chloe Romanis, an assistant professor of Biolaw at Durham University, has recently been considering how connected contraception is to state regulation of reproduction. “For white women the pill has always been a symbol of freedom,” Romanis says, “but that’s just not true for Black women and indigenous women in the United States because it is another vehicle by which the state controlled who was enabled to reproduce and in what circumstances.” She cites Krystale Littlejohn’s book Just Get on the Pill: The Uneven Burden of Reproductive Politics, which examines the complex history between people of colour and long-term contraception because of state violence, and says that any new contraceptive method raises questions “about who this invention is for, and structurally who is likely to bear the brunt of its development.”

Ultimately, while contraceptive tests still revolve around mice not men, all these questions still reside in the realm of fantasy. Yet, perhaps imagining a different reality is half the battle. As Romanis notes, for most of the 20th century, “the focus was, how do we stop the person getting pregnant, as opposed to how do we stop the sperm being viable in the first place. Imagine if there had been just a little less patriarchy in the ways we thought about reproduction only 100 years ago – maybe we would have the male contraceptive pill already”.

*Names have been changed

‘The side effects of female contraceptives are so severe I can’t keep on them until menopause’