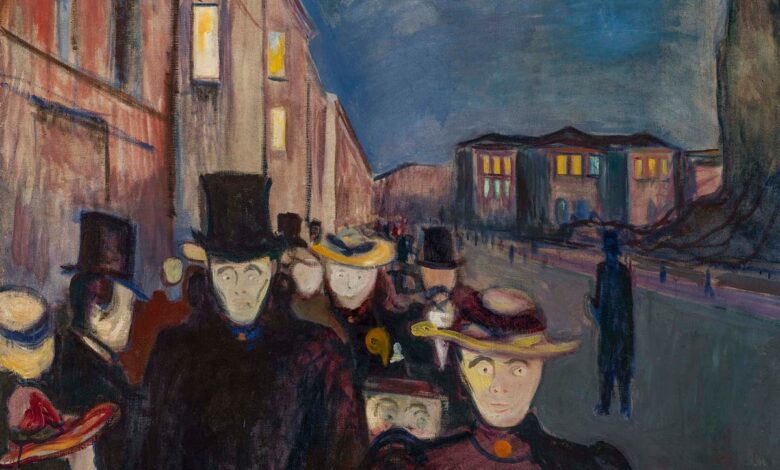

Why we’re all still screaming for Edvard Munch

It’s said that, in old age, the artist Edvard Munch (1863-1944) used to keep the radio on in his house in Oslo 24 hours a day. Often two or more radios played in each room, tuned to different stations – such a dread did he have of silence. This seems apt, given that Munch’s best-known painting by far is The Scream.

That one image has been so easily assimilated into mainstream popular culture – inspiring everything from a well-used emoji on your phone to Macaulay Culkin’s pose for the poster of Home Alone – that it has, to some extent, overshadowed the rest of the artist’s career.

Thankfully, an upcoming exhibition at London’s Courtauld Gallery is offering a look at Munch that will go beyond his most recognised image. It will show the artist in the round, featuring 18 works – 11 of them never seen in the UK before – from the marvellous Munch collection of KODE museum in Bergen, Norway’s second city. These were purchased in the artist’s lifetime by the Bergen-born mill owner and art collector, Rasmus Meyer, and donated to the city after Meyer’s death.

The pictures range across the 25 years generally accepted to represent Munch’s peak: the mid-1880s to 1909 (the latter date marking his nine-month stay in a sanatorium after a nervous breakdown). This quarter-century covers his early flirtation with Impressionism through to finding what became his signature style, Expressionism. The Scream does fall pretty much into that same period, but it’s not part of KODE’s collection. (Munch actually painted two versions of the work: one in 1893, the other in around 1910.)

Fast forward a century and a bit, and the artist is having something of a moment. The Courtauld show comes in the wake of a 2021 exhibition at the Royal Academy, in which a selection of the Norwegian’s art was shown alongside a selection of Tracey Emin’s. The British artist calls herself Munch’s “number one fan” and says that, before coming across his work, she hadn’t been “aware there was art where people could express their emotions”.

Last year also saw impressive auction results for Munch, most notably the sale of his 1904 painting, Summer Day or Embrace on the Beach (The Linde Frieze), for the small matter of £16.28 million at Sotheby’s in London.

What’s more, in October 2021, an enormous new Munch Museum opened – spread across 13 floors and 26,313 square metres – on the Oslo waterfront. It is about four times the size of the original Munch Museum, which opened in the 1960s and was located in a less accessible part of the city called Tøyen.

How to explain this popularity? Well, in part, it’s down to the fact that, like Van Gogh, Munch painted arresting pictures that reflected his equally arresting life.

His childhood was marked by tragedy: he lost both his mother and elder sister Sophie to tuberculosis when he was five and 13 respectively. He could never bear to part with the chair on which Sophie died, and today it can actually be found in the Munch Museum. Edvard’s father was a penniless army medic of strict Pietist faith, who beat his children for even the most minor infraction.

Munch’s adult years weren’t much happier. He suffered with lung problems, alcoholism, agoraphobia and much else besides, including a string of infelicitous romances (he never married or had children).

One relationship – with a woman called Tulla Larsen, the daughter of a wine merchant, to whom he was briefly engaged – even ended in a gunshot wound. The details aren’t clear, but in her biography of the artist, Edvard Munch: Behind the Scream (2005), Sue Prideaux suggests that Tulla fired a pistol at him during a quarrel, resulting in the loss of a good chunk of his left middle finger.

Munch’s personal struggles infused the art throughout his career. Not necessarily in an obvious transcription from life to canvas, but more in his works’ general mood. A fine example from KODE’s collection is Melancholy (1894-96), a painting in which a dispirited male figure, seen in profile, sits broodily on a Nordic shore that sweeps far into the distance behind him.

The artist always insisted that he did “not want to paint pretty pictures to be hung on drawing room walls”, but to produce “an art created of one’s innermost heart”. More often than not, this entailed a simplification of forms and a highly expressive use of colour.

Western art had never seen an emotional outpouring quite like it, and the work derives no little power from the viewer’s knowledge that it was rooted in the artist’s own woes. (It should be pointed out that Munch wasn’t perfect, and his art did occasionally slip into melodrama – at his best, though, he avoided that slip.)

In truth, even those who know nothing of the artist’s life can still appreciate his imagery, concerned as it is with universal themes such as love, sex, jealousy, illness, isolation, guilt, anguish, despair and death. The post-coital scene of an uncommunicative, naked couple in Man and Woman (1898) features many of those elements in a single painting.

‘Nude in Profile Towards the Right’ (1898)

As Stein Olav Henrichsen, the director of the Munch Museum, put it at the opening of his new building: “You don’t need a PhD to enjoy Munch… He is dealing with the [things] that we all have to face in life”.

All of which may be true, but it doesn’t explain why the artist is so favoured right now, in the 2020s. Another major exhibition is on at the moment, incidentally – Edvard Munch. In Dialogueat the Albertina Museum in Vienna – which focuses on the Norwegian’s influence on several present-day artists, such as Peter Doig, Marlene Dumas and Georg Baselitz (as well as Andy Warhol).

Perhaps part of the explanation for Munch’s current popularity is that it’s a knock-on effect of The Scream’s own. In 2012, a pastel version of that work from 1895 fetched $119.9 million [£74 million] at Sotheby’s in New York: at the time, the highest price ever paid for an artwork at auction.

The Scream has taken on new life in the 21st century. Its subject howling in distress has become shorthand – in cartoons and memes – for conveying all manner of contemporary troubles, from climate change to Brexit.

‘Man and Woman’ (1898)