Why we’re obsessed with debut novels

Ha ha ha. That’s the sound of the crafty laugh I do, just after I’ve read a really good debut novel. I turn the final page, close the book, and immediately begin to strategise my campaign to tell anyone I like or respect that they should also read it immediately. One) because it’s nice to share. Two) because it makes me look erudite and sophisticated. Much as I love her, bragging about having read Elizabeth Strout’s seventh novel doesn’t make me look edgy or ahead of the pulse. There is, undeniably, a smugness about spotting a great talent first. It makes me feel very self-satisfied. Oh, and I enjoy the books as well.

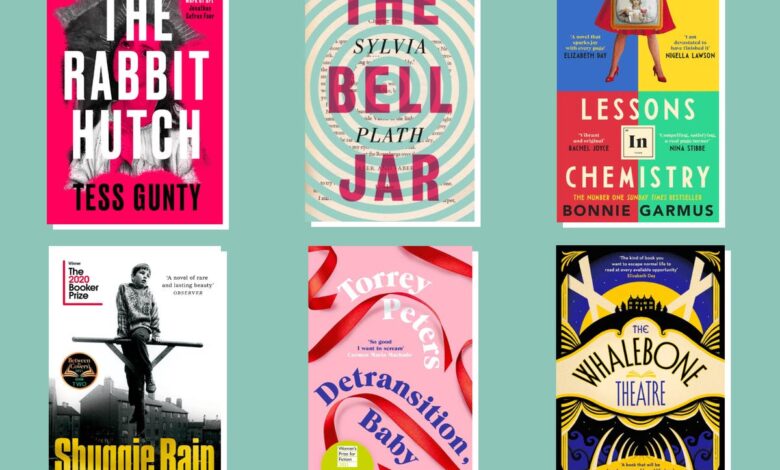

Which is good for me right now, because all of the energy in the world of publishing is decisively behind debuts. This autumn, there are new novels coming from prolific, prize-winning big hitters like Ian McEwan, Elizabeth Strout, Kate Atkinson, Barbara Kingsolver and Maggie O’Farrell. But the buzz so far this year has been around books by new talents. Bonnie Garmus’s Lessons in Chemistry, the endearing story of a headstrong female scientist turned TV cook in the 1950s, has been in the Sunday Times Bestseller list for months. Joanna Quinn’s The Whalebone Theatre, a Cazalet-esque English country house novel, also went straight into the bestseller list after rave reviews.

Many of last year’s best novels were debuts too, from Torrey Peters’ punkish Detransition, Baby to Patricia Lockwood’s very online No One Is Talking About This. Jo Hamya’s Dalloway-esque Three Rooms, about millennial rootlessness, and Virginia Feito’s gothic horror Mrs March flew under the radar, but both deserve to be future classics. And this week, Waterstones announced the shortlist for its first ever Debut Fiction Prize, which will award £5,000 to the winner and throw its weight behind supporting the six new novelists. Garmus has made the list, as has Tessa Gunty’s The Rabbit Hutch, a bewitchingly unique set of interlinked stories that I’m currently racing through. It’s an eclectic list that prides itself on delicious readability above all things.

Debuts have always had an extra frisson because they mark our first encounter with a writer. They may hone their craft, but the first book they put out in the world possesses something raw and electric. We’ll never know what Sylvia Plath would have written after The Bell Jar, but it’s a novel that has stood singularly in its power over generations. Richard Yates may have written a better book in The Easter Parade, but it’s Revolutionary Road that’s embedded in our consciousness for its bewitching portrayal of middle-class malaise in the American suburbs. The Catcher in the Rye was a debut novel. So were Carrie, The Secret History and To Kill a Mockingbird. Debuts are a “sit up and listen” moment, an unignorable “blam!”

In recent years, the growing fixation on debuts has prompted a level of cynicism – the sense that it comes from a flaky publishing world sent mad by Sally Rooney, endlessly trying to replicate her success until it eats itself. “Gossiping about the overhyped debut novelist has become its own kind of contact sport,” wrote author Leslie Jamison in the NYT. It’s that much-mocked search for the “voice of a generation”, a tendency to froth about bidding wars and flashy film rights deals, which suggests an industry with a short attention span, that fetishises youth and doesn’t invest in long-term careers. After all, Bernardine Evaristo’s Booker-winning triumph for Girl, Woman, Other was all the more remarkable given it was her eighth novel and her publishers stuck with her throughout a long, left-field literary career.

Hype aside, for most writers, publishing a novel for the first time will be a vulnerable, hard-won and not necessarily life-changing experience. Debuts don’t have to be synonymous with youth: Garmus is publishing her first book at the age of 64, after working as a freelance copywriter for many years. Douglas Stuart won the 2020 Booker Prize for Shuggie Bain at the age of 43, after it was rejected by 44 publishers. Patience, faith and discipline define their success as much as talent. Besides, a debut doesn’t always guarantee a long career: it’s called the tricky second album for a reason. And even those that make an impression don’t mean writers can quit the day job and live off the fruits of their creative labours. An industry report in 2018 suggested the average earnings for writers was just £10,500 a year. So the support for debut writers is not just nice to see – it’s needed.

But why are debuts thriving right now? We’re living in a multi-platform world, consuming more content than ever. We’re hungry for stories, and we’re more willing to take a risk. Explosive hits in other mediums like I May Destroy You and Fleabag have fed the appetite for new voices. And book sales are on the up. The lockdown-inspired spike in reading has been sustained: according to data from Nielsen BookScan, book sales totalled £767.7m in the first half of this year, the highest since records began, and 25 per cent of that is fiction. We’re very much in a moment of passing the baton, looking for new voices and perspectives. Not just to widen the playing field, but because we’re ready for stories that are new and different. We’re in a moment of transition, an era looking for our cultural totems, time capsules to show who we were and where we are. We want to find our Trainspotting, our White Teeth, our Wasp Factory, our God of Small Things.

But debut novels only go on to cult status because people read them. And then tell other people to read them. It’s a succession of people like me, closing the book and drawing up a list of pals to agitate. The Waterstones’ prize has been chosen by booksellers – people who love books and read a lot. Because after the buzzy marketing campaigns and the fancy film deals, debuts stand the test of time because of good old-fashioned word-of-mouth. There’s a unique joy in discovering a brilliant new writer and breathlessly recommending them to your favourite friends. And there’s another extra treat too – the promise of great books to come. Or, as Jamison says, “the embryonic blueprint of what we can’t yet imagine”.