James Acaster: ‘All my stand-up was in this exaggerated persona – I’m more myself now’

Everyone thought James Acaster had quit stand-up comedy. He said he’d be “glad” to never do it again. Except… today he tells me something different. “I wasn’t going to decide one way or another,” he says from his home in London. Really? But the five-time Edinburgh Comedy Award nominee told one podcast: “Right now, I don’t want to do it again, ever.” His mindset at the time, he says, was about “not putting the pressure on myself to say ‘I have to go back’ or ‘I must never go back’… I never said I’d quit. Some people were under the impression that I did quit, but I really didn’t.”

There were multiple reasons for Acaster not-quite-quitting comedy. His 2019 tour Cold Lasagne Hate Myself 1999 saw him at his most vulnerable on stage, speaking candidly about his mental health. But fame had brought with it an increased number of hecklers who, when combined with the personal material, were hard to handle. I was in the audience for the taping of Cold Lasagne in 2019, and it certainly felt like it could have been Acaster’s last ever show.

I mention this to him and he nods. “When you would have seen it, that was the last time I did the show and I was definitely ready to not do stand-up for a bit and just have a break,” he says. But it was always intended to be just that – a break. The pandemic certainly made it seem more permanent, but in reality, he was probably “taking the same amount of time off as most people”.

Now, Acaster is returning on his own terms. He’s spent the last few months popping up at random shows across the UK, and just last week he announced a run of US tour dates for his new show (fittingly titled Hecklers Welcome). It was news that prompted a collective sigh of relief from his fans.

Since the release of his Netflix Special series Repertoire in 2019, Acaster has graduated from his status as a popular member of the UK panel-show circuit to being the internet’s favourite comedian. Despite his total lack of social media presence, clips of him discussing Brexit and Piers Morgan frequently go viral. He’s cultivated a brand of comedy that punches up at those in power, never down, and has won over fans around the world with his unique brand of comedy – “Your modern, up-to-the-minute, hipster humour”, as Rob Brydon called it on Acaster and Ed Gamble’s food podcast Off Menu.

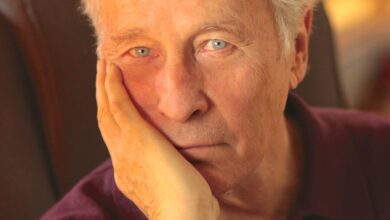

Acaster began performing comedy in his early twenties in 2008, switching from dreams of performing in bands in his hometown of Kettering to stand-up. Some of his first major gigs were supporting Josie Long and Milton Jones on their respective tours. They taught him the importance of cultivating an onstage persona, which has been a crucial part of Acaster’s comic alter ego. While performing, Acaster walks with a mischievous swagger and speaks quickly and confidently, his distinctive voice constantly fluctuating in pitch and peculiar cadences. The person before me on Zoom is far more subdued. His tone is lower and he chooses his words deliberately as he sinks deep into his sofa.

The internet may have been instrumental in Acaster’s global success, but the comedian’s own relationship with social media is more distant. He gave it all up in 2019 and is now releasing the parody self-help guide James Acaster’s Guide to Quitting Social Media: Being the Best YOU You Can Be and Saving Yourself from Loneliness, Vol 1.

Written in the tone of the motivational speakers constantly being served to him by the YouTube ad algorithm, the book sees Acaster preach about his imagined life on and off social media: how he stumbled upon MySpace while looking for the gardening website MySpade.com; how a short stint in prison can actually be a good way to go offline. In reality, he gave up because he was simply bored of the whole thing. The book was a tongue-in-cheek way of mocking the people who go offline and profess their life to be so much better, “like before social media existed, everyone was fine”.

Acaster knew that those online gurus were “objectively poisonous, preying on people in vulnerable positions”, yet he found them oddly fascinating. “It was always a different person every time, sitting in a really expensive car, saying, ‘A year ago, I was sleeping in a bin and now I’m here and I’m gonna tell you how you could do it the same.’” Their main skill? An ability to talk in a stream of consciousness without saying “um” or “err” or “you know”. Acaster pauses. “And I mean, that’s a lesson to all of us. If you learn to never say those kinds of things… I think it opens a lot of doors for you.”

The book may be written from a fictional character’s perspective, but it’s impossible not to read it in Acaster’s voice – or, at least, that onstage voice. “All my stand-up was in this exaggerated persona, but sometimes I’m a bit more myself now. The line’s a bit more blurred,” he says. Does he feel like people expect him to be more energetic when they meet him? He considers. “Sometimes you get people being like, ‘Oh, I thought you’d be funnier in real life’ [or] they will respond in a way like that’s what they wanted and you’re not giving it to them. But that’s their thing. That’s not mine… If I’m not in full persona asking them ‘Poppadoms or bread?’ [his catchphrase on Off Menu], it’s up to them to be OK with that.”

Acaster much prefers these interactions to feeling “constantly available” to fans on social media, anyway. Yes, they could message him every day on Instagram and read about what he’s having for breakfast on Twitter, but it’s a false, one-sided conversation. He explains: “Even for them, that’s not actually as fun as they think it is. It’s like having the same food every day. You’re just constantly eating a Mars bar every day, and actually, maybe it’s nice to have a Mars bar as a treat every now and again. So I’m comparing myself to a chocolate bar now,” he jokes self-deprecatingly.

Acaster has worked hard to open up on stage, but he doesn’t want to depend on his audiences for emotional validation. In Cold Lasagne, which Acaster released as a pay-to-watch special in 2019, the comedian spoke at length about his mental health: the show culminated in a story about him phoning the Samaritans in the middle of filming a much-memed charity special of The Great British Bake Off. On stage, Acaster says that these are feelings he’s worked through. And then he jokes: “Don’t take this badly, but you lot are never gonna be the first people I come to.”

The line was important for two reasons. Firstly, to stop the “patronising” expressions of pity he was getting from audiences while discussing his mental health. And, more importantly, to show his fans, many of whom have similar struggles, that it can get better. “I think it does help to have someone go, ‘Oh, by the way, I don’t feel like that now. I did, but now I don’t,’” he says. “I really didn’t want to romanticise that kind of stuff and encourage people to just stay in it. I wanted to talk about doing the work, going to therapy, but doing the work in any way that you can… Letting people know at the end of the show that things aren’t like that any more.”

Releasing Cold Lasagne independently rather than on an existing streamer was a risky decision for Acaster. But given the personal nature of the content, he wanted to maintain as much ownership as he could. “All the wording in the show is as precise as I can possibly make it so that I can’t be misinterpreted by the audience,” he explains. “I was very aware that, if you release it, there’ll be people … who will post about it online out of context, and there’ll be people whose only experience of the show is the out-of-context clips, or memes, or quotes, and it will become something different.”

There is one clip from Cold Lasagne, however, that does do the rounds on Twitter. In it, Acaster sets his sights on so-called “edgy” comedians who have built their brands around “challenging” material “slagging off transgender people”. “Oh yeah, because you know who’s long overdue a challenge? The trans community,” he jokes. He then makes a confession: “I used to name one of the comedians that was about in that routine, but it always got really awkward in the room. Because apparently, it’s 2019. Most people? Still more than happy to laugh at transgender people. Not as comfortable laughing at Ricky Gervais.”

There are so many brilliant trans comedians working today, and many writers and think-pieces being written about [transphobia] that are way more articulate than me

The clip reappears whenever Gervais, Dave Chappelle, or any other comedian releases a new special that includes jokes about transgender people. How does Acaster feel knowing that this video, removed from the context of the show, is shared in this way? A pause. Acaster carefully considers his answer; he seems deliberately to avoid saying Gervais’s name. “Well, I’m definitely glad that the clip used is the clip in its entirety… It’s kept in context, so that’s great.” Friends will often message him and ask if he’s OK with fans of those comedians criticising him, but “I’m not seeing any of it, and also, I don’t mind. If it’s people who disagree with that statement, then I don’t really mind if they’re getting angry about it or hating me.”

What he really hopes is that well-meaning fans don’t just look to people like him – or “brave little cis boys”, as he says in the special – for commentary on transphobia in comedy. “It’s all well and good, my comedy routine about it, [but] people sometimes talk about it like it’s the thing that people keep on holding up in the argument. I know that the argument is one group of comedians saying this stuff and so people fire back with a clip of another comedian, and I get how that’s relevant, and I am specifically talking about them. But there are so many brilliant trans comedians working today, and many writers and think-pieces being written about the subject that are way more articulate and better than me wearing a pair of aviator sunglasses and a sunset jacket.”

After recording Cold Lasagne in December 2019, Acaster took his break from stand-up. The tour had been a tricky one. He’d gone into it excited to let go of some of that onstage persona and talk about his real life. By the end, audience members were writing online that Acaster was spending large chunks of every show engaging with his hecklers, unable to ignore their shouts.

What that time allowed him was an opportunity to work on his relationship with the audience, get a handle on hecklers, and think about how he can protect his mental health on stage. “I’m going into it knowing, ‘Here are the things that I really didn’t enjoy before, so let’s focus on those things and let’s focus on making that better, and making that aspect of my performance better,’” he says. “To now pick it up from there and go, ‘OK, I don’t like all those things, but what are we going to do about that? How are we going to make sure those things don’t ruin it for you?’ – that’s been really positive.” And then, Acaster says something that wouldn’t have felt possible a year ago: “I’ve got a gig tonight and I’m looking forward to it.”

Acaster on ‘Celebrity Mastermind’